Pale Blue Auto-Mobile

Pale Blue Auto-Mobile

Wednesday, April 26, 2006

Click Here for an Associated Press (AP) article and podcast on the ULA's Howl protest at Columbia U. It includes some discussion of Jelly Boy and how he mousetrapped his own tongue in the service of literary protest!

(AP Photo/HO Geoff Hall)

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

It may have been the Underground Literary Alliance's most successful protest action ever staged. Read part of a preliminary report from King Wenclas below and click through to the ULA site for more info on the night the ULA Howled.

There's no other way to depict it except as a success after we presented a wide variety of underground writers, with wild entertainment, to an enthusiastic crowd outside Columbia U's Miller Theater last night. We showed what genuine literature connecting to the general public is about. We made our point, easily distributed large stacks of informational flyers to members of our very curious audience, and brought underground writers together with New York journalists.

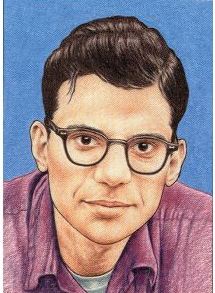

(Picture -- Young Ginsberg by Crumb)

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

"No more time to tell how,

This is the season of what."

The Eleven -- The Grateful Dead

Jack Saunders' Chapbook Free Speech for the ULA's Howl Protest at Columbia U., NYC.

This is the season of what."

The Eleven -- The Grateful Dead

Jack Saunders' Chapbook Free Speech for the ULA's Howl Protest at Columbia U., NYC.

Monday, April 17, 2006

Ginsberg's "Howl" is Fifty This Year

WNYC Newsroom

NEW YORK, NY April 17, 2006 —This year marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of Allen Ginsberg's epic Beat poem "Howl" which dealt frankly with homoeroticism, drugs, music and politics. It sparked an obscenity case which ended with the legal precedent of "redeeming social value" for a literary work.

There's a celebration tonight at Columbia University where Ginsberg was a student. The anti-establishment writers group, the Underground Literary Alliance, is protesting some of the speakers as well as the admittance fee saying it goes against the spirit of the beat generation.

http://www.wnyc.org/news/articles/59240

WNYC Newsroom

NEW YORK, NY April 17, 2006 —This year marks the 50th anniversary of the publication of Allen Ginsberg's epic Beat poem "Howl" which dealt frankly with homoeroticism, drugs, music and politics. It sparked an obscenity case which ended with the legal precedent of "redeeming social value" for a literary work.

There's a celebration tonight at Columbia University where Ginsberg was a student. The anti-establishment writers group, the Underground Literary Alliance, is protesting some of the speakers as well as the admittance fee saying it goes against the spirit of the beat generation.

http://www.wnyc.org/news/articles/59240

From Today's Columbia Spectator

But in academia, which has become the only real sanctuary for poets and poetry in America, “Howl” is still largely unread; the poem that won the legal battle in the courtroom lost the culture war in the classroom. Students of poetry, including those at Columbia, have been poorer off, and perhaps safer, too, from an intentionally provocative poem that explicitly attacks capitalism, the FBI, and war and that idealizes and romanticizes the lost, the lonely, and the outcast. After 50 years, “Howl” remains controversial in what it has to say and how it says it—by its serious subject matter and its simultaneous playfulness with words.

But in academia, which has become the only real sanctuary for poets and poetry in America, “Howl” is still largely unread; the poem that won the legal battle in the courtroom lost the culture war in the classroom. Students of poetry, including those at Columbia, have been poorer off, and perhaps safer, too, from an intentionally provocative poem that explicitly attacks capitalism, the FBI, and war and that idealizes and romanticizes the lost, the lonely, and the outcast. After 50 years, “Howl” remains controversial in what it has to say and how it says it—by its serious subject matter and its simultaneous playfulness with words.

The original, authentic Howl reading...

"On October 13, 1955, Elvis Presely played the City Auditorium in Amarillo, Texas -- just one of the countless stops en route to the hysterical adulation he was to experience after signing to RCA-Victor the following month. That same night, far away in San Francisco, six poets -- Kenneth Rexroth, Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Phil Whalen, Philip Lamantia, and a teenaged Michael McClure -- read their work at the Six gallery on Fillmore street, creating such a storm that Jack Kerouac, no less, described the event as 'the night of the birth of the San Francisco poetry Renaissance.' Ginsberg, a twenty-eight-year-old native New Yorker who'd made San Francisco his adoptive city, gave a reading of his epic Blakean poem, Howl. It was to be a foundation stone of Beat subculture.

In truth, the two events weren't so far apart as moments of resistance to the stifling, desensualized dullness of American life in the fifties. The readings were as much a part of the dawning of rock'n'roll as were Presley's scandalous gyrations -- his manner, style, and delivery rooted in black R&B. (It was with good reason that Norman Mailer identified the followers of the Beat generation as 'white Negroes.') 'This was a time of cold, gray silence,' Michael McClure was to write. 'But inside the coffee houses of North Beach, poets and friends sensed the atmosphere of liberation...we were restoring the body, with the voice as the extension of the body.'"

From: Beneath The Diamond Sky -- Haight-Ashbury 1965-1970 by Barney Hoskyns

"On October 13, 1955, Elvis Presely played the City Auditorium in Amarillo, Texas -- just one of the countless stops en route to the hysterical adulation he was to experience after signing to RCA-Victor the following month. That same night, far away in San Francisco, six poets -- Kenneth Rexroth, Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Phil Whalen, Philip Lamantia, and a teenaged Michael McClure -- read their work at the Six gallery on Fillmore street, creating such a storm that Jack Kerouac, no less, described the event as 'the night of the birth of the San Francisco poetry Renaissance.' Ginsberg, a twenty-eight-year-old native New Yorker who'd made San Francisco his adoptive city, gave a reading of his epic Blakean poem, Howl. It was to be a foundation stone of Beat subculture.

In truth, the two events weren't so far apart as moments of resistance to the stifling, desensualized dullness of American life in the fifties. The readings were as much a part of the dawning of rock'n'roll as were Presley's scandalous gyrations -- his manner, style, and delivery rooted in black R&B. (It was with good reason that Norman Mailer identified the followers of the Beat generation as 'white Negroes.') 'This was a time of cold, gray silence,' Michael McClure was to write. 'But inside the coffee houses of North Beach, poets and friends sensed the atmosphere of liberation...we were restoring the body, with the voice as the extension of the body.'"

From: Beneath The Diamond Sky -- Haight-Ashbury 1965-1970 by Barney Hoskyns

FYI -- Greil Marcus (A culture historian whose opinion I hold in high regard) gave Mr. Shinder's book The Poem That Changed America: Howl Fifty Years Later a negative review in The Times.

(c)The New York Times

April 9, 2006

Classic Beat

Review by GREIL MARCUS

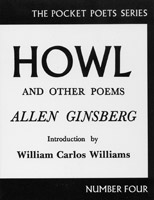

A "HOWL" photograph, taken at the Virginia Military Institute in 1991 by Gordon Ball: a row of uniformed cadets, their heads shaved, each with an identical blank notebook, each holding a copy of the City Lights Books Pocket Poets Series edition of Allen Ginsberg's "Howl and Other Poems," published in San Francisco in 1956, subject to an obscenity trial soon after, cleared by Judge Clayton Horn in a ringing affirmation of individual liberty and creative expression — and a flag of revolt, a blow against conformity, a hallowed relic, ever since.

The picture is all irony. What are these presumed soldiers of Moloch — the demon of money and power summoned in the second part of "Howl" to devour the soul rebels of the epic first section, unless, somehow, they can escape to fight another day — supposed to make of Ginsberg's celebration of a tiny band of comrades determined to free America from itself? Of his paeans to men who "screamed with joy" as they were penetrated by other men, to heroin and marijuana, to suicide and madness? Who knows what the cadets made of "Howl" — in the picture, they look bored. Another assignment to get through.

Ball, a longtime friend and editor of Ginsberg's, is himself one of 24 contributors to Jason Shinder's collection of new essays on "Howl" (not counting Ginsberg, with his own comment on the poem, written in 1986, 11 years before his death, and John Cage, with his galvanic "Writing Through Howl," also from 1986). Like so many of the writers here, Ball forgivably fetishizes the little City Lights book. Like an 18th-century broadside, it was cheap, it was portable, you could read it standing up on a bus and give it away when you got off. It was a key to the enormous readership "Howl" has gathered over the decades, and you can still pick up a used copy for a dollar or so. But like so many, he gropes for something to say. The literary nakedness of the beats, Ball says of beat heroes like Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, Neal Cassady and the few and then the many who took up the cause, "has something to do with the fact that today national debate includes, as legitimate topics for discussion, things such as homosexuality and heroin addiction." This is close to babble — equating homosexuality and heroin addiction, and ignoring the fact that to the degree that homosexuality is today part of our national debate, it is precisely because one side of the debate believes homosexuality is not a legitimate topic of discussion — but not so close as Ball on the "spiritual base" at "the heart of the Beat Generation," which "may offer a redemption of the woeful American legacy projected by Walt Whitman 125 years ago."

Shinder, Ginsberg's friend and assistant, a poet ("Among Women") and a packager (the editor of "Divided Light: Father and Son Poems" and other anthologies), has produced a tribute album — but a tribute album in which half of the contributors are covering the same song. Rather than "critical texts," Shinder wanted "personal narratives" from well-known writers on "how the poem changed their lives": thus the word "I" appears in the first or second line of more than half the pieces here. The famous first lines of "Howl" are quoted from at least 11 times.

This gets tiresome. Sven Birkerts, bidding fair to replace Rick Moody as Dale Peck's "worst writer of his generation," offers an unbearable template: "Can I possibly convey how those words" — the first lines of "Howl" — "moved in me, how that cadence undid in a minute's time whatever prior cadences had been voice-tracking my life?" No, he can't. He wanders on, into "the moment of Shakespearean ripeness." "Ripeness" would do the job, but you get the feeling it's important to Birkerts to remind us he knows Shakespeare — or maybe to equate his reading "Howl" with Edgar's revelation in "King Lear."

As it happens, it's with the critical pieces that Ginsberg's poem comes back to life — critical pieces that take the shape of real talk. With David Gates there's an instant change in tone. "I drove to the store the other day" — and you realize he's not going to tell you he discovered "Howl" there. He parks, hears the boom of an obscene rap song from the S.U.V. in the next spot and starts thinking: "Banned literary mandarins such as Joyce and Nabokov may simply have wanted to go about their hermetic work unmolested, but Ginsberg was a public poet and a provocateur. 'Howl,' for all its affirmations, is a profoundly oppositional poem, and it counts on being opposed. . . . It's a radically offensive poem, or used to be — offensive even to received notions of what poetry is, and it needs offended readers whose fear and outrage bring it most fully to life."

Ginsberg wrote "Howl" in San Francisco and Berkeley; he read the long first section in public for the first time in San Francisco in 1955, and the whole of the poem for the first time in Berkeley the next year. (A CD of that performance is included in this book.) All sorts of divisions, exclusions, restrictive manners and deferences that were second nature in the East were missing in the Bay Area. If the primary terrain of the poem is New York City, the freedom one could find in California in the 50's is crucial to the air that blows through the dank rooms of "Howl," blowing all the way back to New York — but you wouldn't know it from the Eastern writers Shinder has brought together, as if such Bay Area poets and critics as Ishmael Reed, Robert Hass, Rebecca Solnit, Joshua Clover or Richard Candida Smith would have less to say about where "Howl" came from and where it went than Jane Kramer and Eileen Myles, who have plenty to say. The America that gets changed in "The Poem That Changed America" is a Steinberg map, with San Francisco as far away as Tangier. "No one," Marjorie Perloff says off-handedly, but too revealingly, "New Yorker or foreigner. . . . "

You can forget that when Luc Sante begins to tell his tale — from 437 East 12th Street, which is, as it happens, the same New York City building where Ginsberg lived. As if rising from the swamp of Eliot Katz on "Political Poetics" (right off, with Katz's invocation of a poet attempting "to envision and create a more humane world," you somehow know this is going to be the longest piece in the book), Sante changes the discussion as if throwing open a door: "Was 'Howl' the last poem to hit the world with the impact of news and grip it with the tenacity of a pop song?" The language is burning, the ideas are jumping and, finally, you are brought into the adventure of the poem, Ginsberg and his fellows turning New York City into their own frontier, then heading west, through Kansas, into Colorado, to the coast, then back again, discovering, you can feel, more of America in the decade before Ginsberg wrote the poem in 1955 than de Soto, Daniel Boone or even Lewis and Clark did in the centuries before them.

"Reading 'Howl' aloud or reciting it," Sante writes, "you could feel the poem giving you supernatural powers, the ability to punch through brick walls and walk across cities from rooftop to rooftop" — faster than a speeding bullet, more powerful than a locomotive, able to leap tall buildings in a single bound, as George Reeves was doing on TV as Ginsberg wrote, just like Scotty Moore's second guitar break in Elvis Presley's "Hound Dog," on Ginsberg's hydrogen jukebox the year that "Howl" first made it into print. Why not? Sante lived for 11 years in Ginsberg's building. He was 36 when he moved out, and when he looks back to that moment, the self-regard of adolescent illumination, so common elsewhere in the pages Sante shares, is replaced by something that doesn't melt at the touch. " 'Howl' probably meant more to me then than ever before," he says, "because finally I could reconcile it with my own experience. 'Poverty' and 'tatters' and 'hollow-eyed' and 'high' were more than poetic figures by then. I could compile my own list of the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness. The decade during which I lived two flights down from Allen was particularly notable for its body count in suicides and overdoses, and those cadavers really had contained some of the best minds I knew. . . . If 'Howl' is a catalog of flameouts and collapses, it is ecstatic in its lamentation. And that is the basic measure of its strength: it is a list of . . . leprous epiphanies as redoubtable as Homer's catalog of ships, but rather than stopping at that, it seizes the opportunity to realize all the botched dreams it enumerates. It envisions every broken vision, supplies the skeleton key that reveals the genius of every torrent of babble, reconstitutes every page of scribble that looks like gibberish the next morning."

Fixed in time in Gordon Ball's photograph, the cadets are still reading "Howl"; they're still fixed in irony. But the story the picture doesn't tell — that, in its way, it protects the viewer from imagining — doesn't end in irony. As Bob Rosenthal, for 20 years Ginsberg's secretary, writes in perhaps the plainest lines in "The Poem That Changed America," only a fool pretends to know what might happen when a poem finds a reader. " 'Howl' still helps young people realize their actual ambitions," Rosenthal writes: "not to become a poor poet living in a dump but maybe to become a physical therapist when you are expected to become a lawyer, or maybe to become a lawyer when everybody expects you to fail at everything."

Greil Marcus is the author of "Lipstick Traces." His new book, "The Shape of Things to Come: Prophecy and the American Voice," will be published in September.

(c)The New York Times

April 9, 2006

Classic Beat

Review by GREIL MARCUS

A "HOWL" photograph, taken at the Virginia Military Institute in 1991 by Gordon Ball: a row of uniformed cadets, their heads shaved, each with an identical blank notebook, each holding a copy of the City Lights Books Pocket Poets Series edition of Allen Ginsberg's "Howl and Other Poems," published in San Francisco in 1956, subject to an obscenity trial soon after, cleared by Judge Clayton Horn in a ringing affirmation of individual liberty and creative expression — and a flag of revolt, a blow against conformity, a hallowed relic, ever since.

The picture is all irony. What are these presumed soldiers of Moloch — the demon of money and power summoned in the second part of "Howl" to devour the soul rebels of the epic first section, unless, somehow, they can escape to fight another day — supposed to make of Ginsberg's celebration of a tiny band of comrades determined to free America from itself? Of his paeans to men who "screamed with joy" as they were penetrated by other men, to heroin and marijuana, to suicide and madness? Who knows what the cadets made of "Howl" — in the picture, they look bored. Another assignment to get through.

Ball, a longtime friend and editor of Ginsberg's, is himself one of 24 contributors to Jason Shinder's collection of new essays on "Howl" (not counting Ginsberg, with his own comment on the poem, written in 1986, 11 years before his death, and John Cage, with his galvanic "Writing Through Howl," also from 1986). Like so many of the writers here, Ball forgivably fetishizes the little City Lights book. Like an 18th-century broadside, it was cheap, it was portable, you could read it standing up on a bus and give it away when you got off. It was a key to the enormous readership "Howl" has gathered over the decades, and you can still pick up a used copy for a dollar or so. But like so many, he gropes for something to say. The literary nakedness of the beats, Ball says of beat heroes like Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, Neal Cassady and the few and then the many who took up the cause, "has something to do with the fact that today national debate includes, as legitimate topics for discussion, things such as homosexuality and heroin addiction." This is close to babble — equating homosexuality and heroin addiction, and ignoring the fact that to the degree that homosexuality is today part of our national debate, it is precisely because one side of the debate believes homosexuality is not a legitimate topic of discussion — but not so close as Ball on the "spiritual base" at "the heart of the Beat Generation," which "may offer a redemption of the woeful American legacy projected by Walt Whitman 125 years ago."

Shinder, Ginsberg's friend and assistant, a poet ("Among Women") and a packager (the editor of "Divided Light: Father and Son Poems" and other anthologies), has produced a tribute album — but a tribute album in which half of the contributors are covering the same song. Rather than "critical texts," Shinder wanted "personal narratives" from well-known writers on "how the poem changed their lives": thus the word "I" appears in the first or second line of more than half the pieces here. The famous first lines of "Howl" are quoted from at least 11 times.

This gets tiresome. Sven Birkerts, bidding fair to replace Rick Moody as Dale Peck's "worst writer of his generation," offers an unbearable template: "Can I possibly convey how those words" — the first lines of "Howl" — "moved in me, how that cadence undid in a minute's time whatever prior cadences had been voice-tracking my life?" No, he can't. He wanders on, into "the moment of Shakespearean ripeness." "Ripeness" would do the job, but you get the feeling it's important to Birkerts to remind us he knows Shakespeare — or maybe to equate his reading "Howl" with Edgar's revelation in "King Lear."

As it happens, it's with the critical pieces that Ginsberg's poem comes back to life — critical pieces that take the shape of real talk. With David Gates there's an instant change in tone. "I drove to the store the other day" — and you realize he's not going to tell you he discovered "Howl" there. He parks, hears the boom of an obscene rap song from the S.U.V. in the next spot and starts thinking: "Banned literary mandarins such as Joyce and Nabokov may simply have wanted to go about their hermetic work unmolested, but Ginsberg was a public poet and a provocateur. 'Howl,' for all its affirmations, is a profoundly oppositional poem, and it counts on being opposed. . . . It's a radically offensive poem, or used to be — offensive even to received notions of what poetry is, and it needs offended readers whose fear and outrage bring it most fully to life."

Ginsberg wrote "Howl" in San Francisco and Berkeley; he read the long first section in public for the first time in San Francisco in 1955, and the whole of the poem for the first time in Berkeley the next year. (A CD of that performance is included in this book.) All sorts of divisions, exclusions, restrictive manners and deferences that were second nature in the East were missing in the Bay Area. If the primary terrain of the poem is New York City, the freedom one could find in California in the 50's is crucial to the air that blows through the dank rooms of "Howl," blowing all the way back to New York — but you wouldn't know it from the Eastern writers Shinder has brought together, as if such Bay Area poets and critics as Ishmael Reed, Robert Hass, Rebecca Solnit, Joshua Clover or Richard Candida Smith would have less to say about where "Howl" came from and where it went than Jane Kramer and Eileen Myles, who have plenty to say. The America that gets changed in "The Poem That Changed America" is a Steinberg map, with San Francisco as far away as Tangier. "No one," Marjorie Perloff says off-handedly, but too revealingly, "New Yorker or foreigner. . . . "

You can forget that when Luc Sante begins to tell his tale — from 437 East 12th Street, which is, as it happens, the same New York City building where Ginsberg lived. As if rising from the swamp of Eliot Katz on "Political Poetics" (right off, with Katz's invocation of a poet attempting "to envision and create a more humane world," you somehow know this is going to be the longest piece in the book), Sante changes the discussion as if throwing open a door: "Was 'Howl' the last poem to hit the world with the impact of news and grip it with the tenacity of a pop song?" The language is burning, the ideas are jumping and, finally, you are brought into the adventure of the poem, Ginsberg and his fellows turning New York City into their own frontier, then heading west, through Kansas, into Colorado, to the coast, then back again, discovering, you can feel, more of America in the decade before Ginsberg wrote the poem in 1955 than de Soto, Daniel Boone or even Lewis and Clark did in the centuries before them.

"Reading 'Howl' aloud or reciting it," Sante writes, "you could feel the poem giving you supernatural powers, the ability to punch through brick walls and walk across cities from rooftop to rooftop" — faster than a speeding bullet, more powerful than a locomotive, able to leap tall buildings in a single bound, as George Reeves was doing on TV as Ginsberg wrote, just like Scotty Moore's second guitar break in Elvis Presley's "Hound Dog," on Ginsberg's hydrogen jukebox the year that "Howl" first made it into print. Why not? Sante lived for 11 years in Ginsberg's building. He was 36 when he moved out, and when he looks back to that moment, the self-regard of adolescent illumination, so common elsewhere in the pages Sante shares, is replaced by something that doesn't melt at the touch. " 'Howl' probably meant more to me then than ever before," he says, "because finally I could reconcile it with my own experience. 'Poverty' and 'tatters' and 'hollow-eyed' and 'high' were more than poetic figures by then. I could compile my own list of the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness. The decade during which I lived two flights down from Allen was particularly notable for its body count in suicides and overdoses, and those cadavers really had contained some of the best minds I knew. . . . If 'Howl' is a catalog of flameouts and collapses, it is ecstatic in its lamentation. And that is the basic measure of its strength: it is a list of . . . leprous epiphanies as redoubtable as Homer's catalog of ships, but rather than stopping at that, it seizes the opportunity to realize all the botched dreams it enumerates. It envisions every broken vision, supplies the skeleton key that reveals the genius of every torrent of babble, reconstitutes every page of scribble that looks like gibberish the next morning."

Fixed in time in Gordon Ball's photograph, the cadets are still reading "Howl"; they're still fixed in irony. But the story the picture doesn't tell — that, in its way, it protects the viewer from imagining — doesn't end in irony. As Bob Rosenthal, for 20 years Ginsberg's secretary, writes in perhaps the plainest lines in "The Poem That Changed America," only a fool pretends to know what might happen when a poem finds a reader. " 'Howl' still helps young people realize their actual ambitions," Rosenthal writes: "not to become a poor poet living in a dump but maybe to become a physical therapist when you are expected to become a lawyer, or maybe to become a lawyer when everybody expects you to fail at everything."

Greil Marcus is the author of "Lipstick Traces." His new book, "The Shape of Things to Come: Prophecy and the American Voice," will be published in September.

Saturday, April 15, 2006

Good job by Billie Cohen in Time Out New York where she featured the ULA and its upcoming Howl protest in an evenhanded way.(And thanks for including a photo I took at the ULA's Medusa reading in Philadelphia last year!)

Click to hear a WNYC radio interview from yesterday with one of the Underground Literary Alliance's poets, Frank Walsh. He's followed by the author of the book The Poem That Changed America: Howl Fifty Years Later. It offers both sides of the issue that has prompted the ULA to put on a protest/free performance at Columbia U. Monday night.

Friday, April 14, 2006

A dissenting opinion on the ULA action:

"I understand the impetus behind the ULA opposing the beat event . . . especially as it is charging a ludicrous cover fee . . . but I don’t see any good coming from picketing, heckling, or even handling out fliers on the sidewalk. The problem is that the average attendee doesn’t have the slightest clue why some of these things might be offensive or warrant criticism."

"I understand the impetus behind the ULA opposing the beat event . . . especially as it is charging a ludicrous cover fee . . . but I don’t see any good coming from picketing, heckling, or even handling out fliers on the sidewalk. The problem is that the average attendee doesn’t have the slightest clue why some of these things might be offensive or warrant criticism."

Tuesday, April 11, 2006

Sunday, April 09, 2006

Plea from a poet

Some time ago the ULA published UK poet Bruce Hodder's Poem For Howl Fifty at Underground Literary Adventures. It communicates the spirit behind the Howl reading protest.

Some time ago the ULA published UK poet Bruce Hodder's Poem For Howl Fifty at Underground Literary Adventures. It communicates the spirit behind the Howl reading protest.

Friday, April 07, 2006

The Outsiders Outside

Jack Saunders, the ULA's own Bayou Baudelaire...Where do you think he will be -- he the possessor of some of the last remnants of the true Beat spirit -- on the evening of April 17 when the academics and establishment publishers and writers at Columbia U. are congratulating themselves on co-opting Allen Ginsberg's HOWL for their use? Do you think he will be all cozy up on stage, an invited representative of the underground that Ginsberg was once all about? Guess again...

Jack Saunders, the ULA's own Bayou Baudelaire...Where do you think he will be -- he the possessor of some of the last remnants of the true Beat spirit -- on the evening of April 17 when the academics and establishment publishers and writers at Columbia U. are congratulating themselves on co-opting Allen Ginsberg's HOWL for their use? Do you think he will be all cozy up on stage, an invited representative of the underground that Ginsberg was once all about? Guess again...

Tuesday, April 04, 2006

HOWL -- For the ULA co-option is not an option...

The proprietor of the blog "You Are Here" is sympathetic to the ULA's stance on the HOWL reading.

The proprietor of the blog "You Are Here" is sympathetic to the ULA's stance on the HOWL reading.

Monday, April 03, 2006

Countdown To HOWL

I am not one for much blog linkage: in general I find little point in cluttering up my blog with links that will be dead in a few months or so. Also, someone has usually gotten there first and I loathe unoriginality, especially if it is my own. (Impossible!)

The point of all this is to alert my readers that there will be significant linkage here until April 17, when the academics, publishers and literati present their reading of Ginsberg's HOWL at Columbia U. in NYC.

I will try to keep you informed about the Underground Literary Alliance's plans to protest the event, as the group believes that the very people who should be a part of this academy/Big Publishing show have been shut out.

The first place to go is to the ULA site to read "Ginsberg's Kent State Interview" by Wred Fright.

While there, check out "Free The Beats" (accessible from the home page) for the who-what-where-when-why on the ULA's protest.

I will also link to other blogs and news stories that deal with the ULA's HOWL protest, so bookmark me. (You can always delete it after the event, when I go back to my usual business of dealing with ne'er-do-well writer J.D. Finch. That is, me.)

Sunday, April 02, 2006

It's a rare comedian who can deliver bad taste jokes with such good taste. But the always tasteful -- even when it's bad -- Jennifer Dziura miraculously pulls it off.

donate your OWN blood; drive-bys don't count

donate your OWN blood; drive-bys don't count